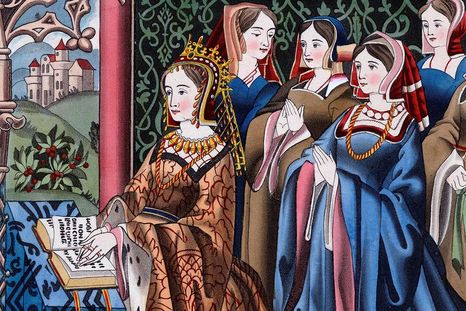

MARGARET OF ANJOU IN THE

ASCENDENT

1455-1459

Margaret of Angou - March 23, 1429 - August 25, 1482

Queen Margaret was an important and pivotal player in the War of the Roses, sometimes referred to as the' Hundred Years War'. She was Queen Consort of Henry VI of England. So influential was she that Shakespeare included her in some his plays.

In 1453, Henry VI was taken ill with what had been described as a bout of insanity; Richard, Duke of York, became Protector, heir to the throne. However, a few years earlier Margaret of Anjou had given birth to a son, Edward (October 13, 1451), changing the succession of the throne. Rumors later surfaced -- useful to the Yorkists -- that Henry was unable to father a child and that Margaret's child must be illegitimate.

The war of the Roses begins in 1454 and this is how it all started.

June With the king ill and now firmly in York's power, York resolves to win the support of the political nation at large. He summons parliament to meet at Westminster in July.

July Parliament passes a bill granting a full amnesty to all members of the Yorkist army at St Albans. York realises that the situation is still far from settled. The king’s health remains precarious and unrest in the south west is beginning to increase. Accordingly, York plans to secure a second term of office as protector when parliament reassembles in November.

November With the strong backing of parliament, Henry VI confirms York as protector. Strong measures are called for to control another flare up in the Courtenay/Bonville feud. With Exeter under the control of Courtenay forces, York moves quickly and peace is restored with the surrender and imprisonment of the Earl of Devon in mid December.

1456

February York’s second protectorate comes to an end when the king recovers his full health and promptly relieves him of his post. However, there appears to be no residual ill will on the king’s part and contemporary writers speak of York and the Nevilles remaining as the most influential group in the council.

March Queen Margaret still regards York as the greatest threat to herself and her son and is determined at all costs to stop a third protectorate. She begins to quietly carve out a sizeable powerbase in and around the midland castles of the royal Duchy of Lancaster.

August King Henry leaves Westminster and joins his wife at Kenilworth. Between now and the end of the year, Margaret ensures that all new court appointments are filled by men whose loyalty to herself and her husband is as reliable as possible.

1457

January The year opens with gradual indications that the political tide is beginning to turn against York and the Nevilles. That said, the speed of the drift is slow.

August A French raiding force lands on the Kentish coast and sacks the port of Sandwich. A real fear of invasion pushes York and Warwick (now captain of Calais) into the spotlight as men of action who can save the situation. The Duke of Buckingham continues to act as a mediator at court and it is through his efforts that York, Salisbury and Warwick agree to pay compensation to the Percy and Clifford families.

1458

24 March The Loveday. This is a misguided attempt by King Henry to get the rival magnates to kiss and make up. All go in procession to a service of reconciliation at St Paul’s, where promises of friendship are sworn. Observant Londoners find this all rather hard to swallow, given the large armed retinues each magnate has conspicuously brought to the city.

May Determined to balance the royal books, Queen Margaret cuts what she considers to be needlessly large subsidies for the Calais garrison. Warwick finds it necessary to resort to piracy to pay his troops. His piratical exploits earn him the admiration of his men and the ire of Queen Margaret.

October Warwick is summoned to London to answer numerous charges of piracy. He is involved in a brawl between his servants and those of the king, a fracas for which Margaret intends he shall take the blame. In defiance of both the queen and government, Warwick flees to Calais.

1459

May Warwick’s actions force people such as the Duke of Buckingham to abandon the middle ground and throw in their lot with the court party.

June A Great Council is summoned by the queen to meet at Coventry, a meeting from which the Yorkist leaders are pointedly excluded. Fearing ‘the malice of the queen’, Warwick, Salisbury and York determine to hold a council of their own at Ludlow. They claim that they still want peace, but that now only a show of force will get them past the hostile court. Both sides begin actively to prepare for war.

2 September Warwick sails from Calais, leaving Lord Fauconberg in command of the remainder of the garrison.

12 September Salisbury sets out from Middleham Castle. His army numbers no more than 5,000, together with his sons Thomas and Sir John Neville and their leading retainers. On or about the same day, several small royalist armies also take the field. Their aim is to prevent Salisbury from joining forces with Warwick, who is marching north to meet him at Ludlow with his own levies and a large component of the Calais garrison.

15 September The king is at Nottingham with a small force, whilst the queen and Prince Edward are at Chester and the Duke of Somerset keeps a watch on the West Midlands.

16 September Warwick evades Somerset and manages to reach Ludlow without further incident. His father is less fortunate and soon has at least two royalist armies moving to intercept him. The earl successfully evades King Henry’s troops, but hears from local Yorkist sympathisers that he is being pursued by those of the queen.

19 September Both armies anxiously wait to see on which side the Stanleys will come down. Lord Thomas Stanley assures Margaret of his support, but in the event keeps a careful distance. By contrast, his brother Sir William comes to the aid of the Nevilles.

22 September Salisbury learns that his route to Ludlow is being blocked by a hastily raised force from Cheshire under the command of Lords Audley and Dudley. He draws up his army, now just under 6,000 strong on Blore Heath near Market Drayton and prepares to offer battle.

23 September The Battle of Blore Heath.

Salisbury arrays his men for battle along a ridge overlooking the Hempmill brook. His left is anchored by a small wood, his right by a larger of wagons. The Lancastrian commanders are overly confident in their 2-1 advantage and order at least two cavalry charges against the Yorkist line. Undeterred, the Yorkist archers (many of whom are veterans of the French wars), coolly loose flight after flight of arrows into the milling mass of men and horses. During the second of these charges, Lord Audley is killed and Lord Dudley orders a general dismounted assault. Despite severe pressure, Salisbury’s men beat off the inexperienced and poorly led Cheshire levies and with the capture of Lord Dudley, the Lancastrian army breaks and runs. Salisbury, however, is in no fit state to pursue and withdraws from Blore Heath as soon as possible. Despite the capture of his two sons and Sir Thomas Harrington, he eventually reaches the safety of Ludlow Castle.

1 October The Yorkist leaders send a letter to King Henry attempting to excuse and justify their actions. The court is prepared to pardon all those who will lay down their arms and bend the knee – except those involved in Audley’s death. However, there is simply not enough trust remaining between the two sides to allow for any compromise.

12 October The Lancastrian army approaches Ludlow from the south, to find the Yorkist army in a blocking position at Ludford Bridge. Even though the Yorkists have their field artillery and have concentrated all their forces, their opponents have two major advantages. Firstly, a large number of the peers are present in their army, whereas the Yorkists only have six. Secondly (and more decisively), the Lancastrian army have the anointed king with them. At this point, the soldiers of the Calais garrison and their commander Andrew Trollope decide that their oath of allegiance to King Henry outweighs any loyalty they have for the Yorkist lords. They desert to the other side en masse, taking with them full knowledge of York’s battle plans for the following day. The Yorkist commanders realise that their cause is hopeless and order their forces to scatter. York and his second son Edmund, Earl of Rutland, make for Dublin. His eldest son Edward, Earl of March, rides south with the Nevilles and with the help of Yorkist sympathisers in Devon makes his way to Calais. The Yorkist flight has been so precipitate that the Duke of York is obliged to leave his wife, Cecily Neville, and his two youngest sons, George and Richard, with instructions to throw themselves on the mercy of Queen Margaret. While all three are taken into protective custody by the Duke of Somerset, Ludlow is punished for its Yorkist sympathies and is pillaged as if it were in France. The Yorkist cause is in ruins and England firmly in the power of Queen Margaret.

Margaret played a pivotal role in the struggle, influencing politics and the Kings decisions. She outlawed the Yorkist leaders in 1459, refusing recognition of York as Henry's heir.

30th December 1460 (Battle of Wakefield) York was killed during a battle, his dismembered head was placed, with a paper crown, to mock him, on a spike at York. He had gone to Sandal, near Wakefield to deal with the Lancastarians who had gathered there. His son Edward, now Duke of York and later Edward IV, allied with Richard Neville, Warwick, as leaders of the Yorkist party.

29th March 1461 Margaret and the Lancastrians were defeated at the battle of Towton. Edward VI, son of the late Richard, Duke of York, became King. Wary of their demise and capture, Margaret, Henry, and their son went to Scotland; Margaret retreated to the safety of France. Here she helped arrange and organise the French to support her and her sons claim for an invasion of England. The forces failed in 1463. Henry was captured and sent to the Tower in 1465.

Warwick, another pivotal player the war, helped Edward IV in his initial victory over Henry VI. After a disagreement with Edward, Warwick changed sides. He then supported Margaret and conspired to restore Henry VI to the throne.

Her final defeat

April, 1471 Margaret retuned to England.

May, 1471 Margaret and her supporters were defeated at the battle of Tewkesbury. Margaret and her son were taken prisoner. Her son, Edward, Prince of Wales, was killed. Her husband, Henry VI, died in the Tower of London, presumably murdered.

Margaret of Anjou was imprisoned in England for five years. In 1476, the King of France paid a ransom to England for her, and she returned to France. She lived in poverty until her death on 25th August 1482 in Anjou.

Queen Margaret was an important and pivotal player in the War of the Roses, sometimes referred to as the' Hundred Years War'. She was Queen Consort of Henry VI of England. So influential was she that Shakespeare included her in some his plays.

In 1453, Henry VI was taken ill with what had been described as a bout of insanity; Richard, Duke of York, became Protector, heir to the throne. However, a few years earlier Margaret of Anjou had given birth to a son, Edward (October 13, 1451), changing the succession of the throne. Rumors later surfaced -- useful to the Yorkists -- that Henry was unable to father a child and that Margaret's child must be illegitimate.

The war of the Roses begins in 1454 and this is how it all started.

June With the king ill and now firmly in York's power, York resolves to win the support of the political nation at large. He summons parliament to meet at Westminster in July.

July Parliament passes a bill granting a full amnesty to all members of the Yorkist army at St Albans. York realises that the situation is still far from settled. The king’s health remains precarious and unrest in the south west is beginning to increase. Accordingly, York plans to secure a second term of office as protector when parliament reassembles in November.

November With the strong backing of parliament, Henry VI confirms York as protector. Strong measures are called for to control another flare up in the Courtenay/Bonville feud. With Exeter under the control of Courtenay forces, York moves quickly and peace is restored with the surrender and imprisonment of the Earl of Devon in mid December.

1456

February York’s second protectorate comes to an end when the king recovers his full health and promptly relieves him of his post. However, there appears to be no residual ill will on the king’s part and contemporary writers speak of York and the Nevilles remaining as the most influential group in the council.

March Queen Margaret still regards York as the greatest threat to herself and her son and is determined at all costs to stop a third protectorate. She begins to quietly carve out a sizeable powerbase in and around the midland castles of the royal Duchy of Lancaster.

August King Henry leaves Westminster and joins his wife at Kenilworth. Between now and the end of the year, Margaret ensures that all new court appointments are filled by men whose loyalty to herself and her husband is as reliable as possible.

1457

January The year opens with gradual indications that the political tide is beginning to turn against York and the Nevilles. That said, the speed of the drift is slow.

August A French raiding force lands on the Kentish coast and sacks the port of Sandwich. A real fear of invasion pushes York and Warwick (now captain of Calais) into the spotlight as men of action who can save the situation. The Duke of Buckingham continues to act as a mediator at court and it is through his efforts that York, Salisbury and Warwick agree to pay compensation to the Percy and Clifford families.

1458

24 March The Loveday. This is a misguided attempt by King Henry to get the rival magnates to kiss and make up. All go in procession to a service of reconciliation at St Paul’s, where promises of friendship are sworn. Observant Londoners find this all rather hard to swallow, given the large armed retinues each magnate has conspicuously brought to the city.

May Determined to balance the royal books, Queen Margaret cuts what she considers to be needlessly large subsidies for the Calais garrison. Warwick finds it necessary to resort to piracy to pay his troops. His piratical exploits earn him the admiration of his men and the ire of Queen Margaret.

October Warwick is summoned to London to answer numerous charges of piracy. He is involved in a brawl between his servants and those of the king, a fracas for which Margaret intends he shall take the blame. In defiance of both the queen and government, Warwick flees to Calais.

1459

May Warwick’s actions force people such as the Duke of Buckingham to abandon the middle ground and throw in their lot with the court party.

June A Great Council is summoned by the queen to meet at Coventry, a meeting from which the Yorkist leaders are pointedly excluded. Fearing ‘the malice of the queen’, Warwick, Salisbury and York determine to hold a council of their own at Ludlow. They claim that they still want peace, but that now only a show of force will get them past the hostile court. Both sides begin actively to prepare for war.

2 September Warwick sails from Calais, leaving Lord Fauconberg in command of the remainder of the garrison.

12 September Salisbury sets out from Middleham Castle. His army numbers no more than 5,000, together with his sons Thomas and Sir John Neville and their leading retainers. On or about the same day, several small royalist armies also take the field. Their aim is to prevent Salisbury from joining forces with Warwick, who is marching north to meet him at Ludlow with his own levies and a large component of the Calais garrison.

15 September The king is at Nottingham with a small force, whilst the queen and Prince Edward are at Chester and the Duke of Somerset keeps a watch on the West Midlands.

16 September Warwick evades Somerset and manages to reach Ludlow without further incident. His father is less fortunate and soon has at least two royalist armies moving to intercept him. The earl successfully evades King Henry’s troops, but hears from local Yorkist sympathisers that he is being pursued by those of the queen.

19 September Both armies anxiously wait to see on which side the Stanleys will come down. Lord Thomas Stanley assures Margaret of his support, but in the event keeps a careful distance. By contrast, his brother Sir William comes to the aid of the Nevilles.

22 September Salisbury learns that his route to Ludlow is being blocked by a hastily raised force from Cheshire under the command of Lords Audley and Dudley. He draws up his army, now just under 6,000 strong on Blore Heath near Market Drayton and prepares to offer battle.

23 September The Battle of Blore Heath.

Salisbury arrays his men for battle along a ridge overlooking the Hempmill brook. His left is anchored by a small wood, his right by a larger of wagons. The Lancastrian commanders are overly confident in their 2-1 advantage and order at least two cavalry charges against the Yorkist line. Undeterred, the Yorkist archers (many of whom are veterans of the French wars), coolly loose flight after flight of arrows into the milling mass of men and horses. During the second of these charges, Lord Audley is killed and Lord Dudley orders a general dismounted assault. Despite severe pressure, Salisbury’s men beat off the inexperienced and poorly led Cheshire levies and with the capture of Lord Dudley, the Lancastrian army breaks and runs. Salisbury, however, is in no fit state to pursue and withdraws from Blore Heath as soon as possible. Despite the capture of his two sons and Sir Thomas Harrington, he eventually reaches the safety of Ludlow Castle.

1 October The Yorkist leaders send a letter to King Henry attempting to excuse and justify their actions. The court is prepared to pardon all those who will lay down their arms and bend the knee – except those involved in Audley’s death. However, there is simply not enough trust remaining between the two sides to allow for any compromise.

12 October The Lancastrian army approaches Ludlow from the south, to find the Yorkist army in a blocking position at Ludford Bridge. Even though the Yorkists have their field artillery and have concentrated all their forces, their opponents have two major advantages. Firstly, a large number of the peers are present in their army, whereas the Yorkists only have six. Secondly (and more decisively), the Lancastrian army have the anointed king with them. At this point, the soldiers of the Calais garrison and their commander Andrew Trollope decide that their oath of allegiance to King Henry outweighs any loyalty they have for the Yorkist lords. They desert to the other side en masse, taking with them full knowledge of York’s battle plans for the following day. The Yorkist commanders realise that their cause is hopeless and order their forces to scatter. York and his second son Edmund, Earl of Rutland, make for Dublin. His eldest son Edward, Earl of March, rides south with the Nevilles and with the help of Yorkist sympathisers in Devon makes his way to Calais. The Yorkist flight has been so precipitate that the Duke of York is obliged to leave his wife, Cecily Neville, and his two youngest sons, George and Richard, with instructions to throw themselves on the mercy of Queen Margaret. While all three are taken into protective custody by the Duke of Somerset, Ludlow is punished for its Yorkist sympathies and is pillaged as if it were in France. The Yorkist cause is in ruins and England firmly in the power of Queen Margaret.

Margaret played a pivotal role in the struggle, influencing politics and the Kings decisions. She outlawed the Yorkist leaders in 1459, refusing recognition of York as Henry's heir.

30th December 1460 (Battle of Wakefield) York was killed during a battle, his dismembered head was placed, with a paper crown, to mock him, on a spike at York. He had gone to Sandal, near Wakefield to deal with the Lancastarians who had gathered there. His son Edward, now Duke of York and later Edward IV, allied with Richard Neville, Warwick, as leaders of the Yorkist party.

29th March 1461 Margaret and the Lancastrians were defeated at the battle of Towton. Edward VI, son of the late Richard, Duke of York, became King. Wary of their demise and capture, Margaret, Henry, and their son went to Scotland; Margaret retreated to the safety of France. Here she helped arrange and organise the French to support her and her sons claim for an invasion of England. The forces failed in 1463. Henry was captured and sent to the Tower in 1465.

Warwick, another pivotal player the war, helped Edward IV in his initial victory over Henry VI. After a disagreement with Edward, Warwick changed sides. He then supported Margaret and conspired to restore Henry VI to the throne.

Her final defeat

April, 1471 Margaret retuned to England.

May, 1471 Margaret and her supporters were defeated at the battle of Tewkesbury. Margaret and her son were taken prisoner. Her son, Edward, Prince of Wales, was killed. Her husband, Henry VI, died in the Tower of London, presumably murdered.

Margaret of Anjou was imprisoned in England for five years. In 1476, the King of France paid a ransom to England for her, and she returned to France. She lived in poverty until her death on 25th August 1482 in Anjou.